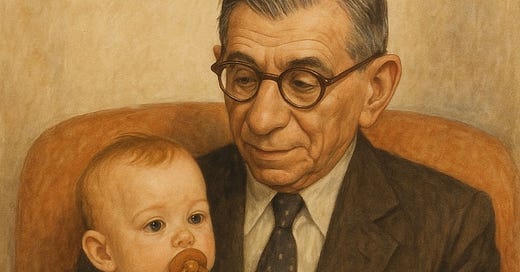

My paternal grandfather died when I was almost three. I think of him standing in a hallway. The lighting was yellowish, and the walls were off-white. There was a hallway like this in his

apartment. He was facing me, almost directly, and was wearing horn-rimmed glasses. He had a strong face, but it was kind. He was supposedly a lovely man and a talented violinist. A psychologist friend told me it was doubtful that I could remember Sam Dezenhall from such a young age.

I found a framed photo of him not long ago in a cabinet in my house. His face appeared very much like it had in my memory. He wore the same glasses. I recalled exactly where this photo had been placed on the wall in the hallway of my childhood house, three-quarters of the way from my bedroom to my parents’. It occurred to me that the walls in this hallway were also off-white, and the light from the ceiling gave off a yellowish glow. In all likelihood, I had not retained a memory of Pop Pop Sam, but I wanted to believe I did and borrowed memories from related things I had seen.

I’m sure that over the years, I have told people I had known him. Had I been lying? This notion bothers me, as it implies a level of malice that was not present. Nevertheless, it hadn’t been the truth either. So, what was it? Maybe it could be called a “false memory” anchored in a deep desire for something to be true because it was pleasant.

Throughout my two careers, as a crisis consultant and a writer, I have been lied to frequently. There is a level of malice that applies to some of what people have told me because there was an intent to mislead. However, I also believe some of these people convinced themselves through some process of self-hypnosis that they were telling the truth.

Executives involved in malfeasance need to believe they are good people who did not do what they did. It’s not like the movies, where bad actors proceed like a James Bond villain glorying in their wickedness. This does not justify their actions, but it helps explain how they got there. If we’re going to understand darkness, we must understand the building blocks of how one gets up to no good.

I am lied to when I research and write about gangsters (and spies). I have been told this same whopper by dozens of people: “Meyer Lansky used to bounce me on his knee when I was a little kid.” Sometimes, there is a slight variation, and it involves a friend or cousin (Lansky was one of the great powers in American organized crime in the 20th Century).

Now get this: I have been approached by many people over the years to write their gangster story. These people claimed to be the offspring, literal or figurative, of legendary gangsters. Sometimes, they assert something like, “Frank Costello saw me like a son.” I have never taken any of these people up on their offers because I don’t believe a single one is telling the truth.

Let’s try to learn something here. These people with their underworld claims all needed to believe they had a fearsome protector. This is memetic because there is no way all these people contacted each other to plot this out. Rather, each of them had: 1) a pre-existing psychic need for protection (most of us do) 2) an interest in organized crime 3) possibly a tangential encounter with something or someone gangland-related and 4) heard a story that resonated deeply with them, consciously or not, and adopted it for their purposes.

There is a phenomenon called the “Mandela Effect,” named after a widespread misperception that South African leader Nelson Mandela died in the 1980s, when in fact he died in 2013. Similarly, most people believe that fictional cannibal Hannibal Lecter greeted the ambitious FBI agent Clarice Starling with a creepy, “Hello, Clarice,” when the killer simply said, “Good morning.” We don’t know how these things got started any more than we understand why a school of fish suddenly turns left, but we can assume there is a collective emotional cascade rooted in a common need.

For a long time, I held my fabulists in contempt, both because they were dishonest and because they wasted my time and insulted my intelligence. However, I then think about my memory of my paternal grandfather, which is likely inaccurate (I knew my other grandfather, Joseph Byer, very well). It is not, however, malicious, and no one got hurt except perhaps me. I also wonder how much of what I remember about other stuff may not have happened the way I think it did. Nor do I rule out the possibility that my interest in some of the colorful characters who haunted my boyhood stems from an unconscious desire to have been protected by them, which I never was, not for a second. So, what good were they? Maybe they were just crooks.

What lends credibility to my self-analysis is the reaction people have when they find out I write about scary guys. They uniformly think it’s cool and poke around at notions that I could deploy these rapscallions in a badass way. In other words, Don’t mess with THIS GUY, the message all of us, at a primal level, would like to send to the world. There isn’t a dude who has watched The Godfather, Part II who hasn’t fantasized about delivering the line Michael Corleone uses on the extortionist politician: “You can have my answer now, Senator. My offer is this: nothing.” The truth is that almost none of us have ever had the opportunity to utter such a line, which is why the fantasy is so potent.

In the meantime, my research has turned up no evidence that Meyer Lansky was ever running a daycare center. However, I did hear a story about Lansky and a few gangster pals babysitting a niece while her parents went out. Who knows if it’s true, but I want to believe it is, which is why it stays with me.

Like the famous line from Casablanca, “Play it again, Sam.” (No one says those words).